Why AI Strategy Is Really an Org Design Problem

Updated:

4 minutes

I used to think AI strategy was mostly about technology choices. Models, platforms, data foundations, governance. Get those right, and the rest would follow. Over time, that belief became harder to defend. Not because the technology stopped working, quite the opposite, but because the organizations around it didn’t change in the ways that mattered.

What kept showing up, across companies and contexts, was the same quiet pattern: AI initiatives stalled not at the point of capability, but at the point of responsibility. This is part of a broader pattern I explored in The AI Strategy Gap: most companies think they have an AI strategy, but they really just have a roadmap of AI features. The gap isn’t technical—it’s organizational.

When AI works, but nothing happens

In many organizations, AI works exactly as advertised. The models are accurate. The dashboards are insightful. The recommendations are reasonable. And yet, very little changes.

Decisions are still made the same way. Processes still move at the same speed. Escalations still follow the same paths. AI becomes something people consult, not something that meaningfully reshapes how work gets done.

That gap is rarely technical. It’s organizational.

The subtle comfort of centralization

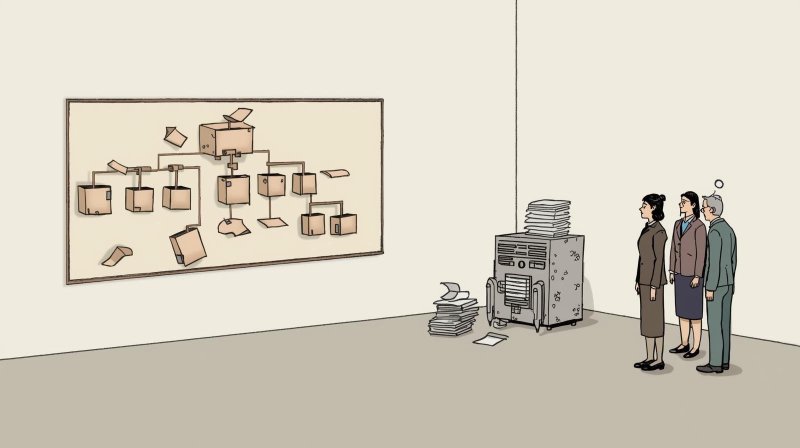

A common response is to centralize. Create an AI team. A center of excellence. A platform group. Something that can “own” AI on behalf of the organization. There is a real comfort in this move. It signals seriousness. It reduces visible chaos. It creates a place where complexity can live without disturbing the rest of the system.

But it also creates distance. Distance between insight and action. Between domain knowledge and execution. Between accountability and authority.

Over time, AI becomes someone else’s responsibility — and therefore no one’s.

AI doesn’t introduce new problems, it reveals old ones

AI has a way of surfacing questions organizations have learned to work around:

- Who actually owns this decision?

- What happens when recommendations are ignored?

- Which risks are acceptable, and who carries them?

- When does speed matter more than consistency?

Before AI, these questions could remain implicit. Humans compensated. Ambiguity was absorbed through meetings, judgment calls, and informal escalation.

AI is less forgiving. It asks for clarity — or it quietly becomes irrelevant.

From intelligence as a service to capability as a habit

One of the more subtle shifts I’ve seen in organizations that make progress is how they think about where AI capability belongs.

Early on, AI is often treated as a service. A centralized team builds models, exposes insights, delivers dashboards or APIs. The rest of the organization consumes them. This feels efficient, even elegant. Intelligence is produced in one place and distributed elsewhere.

But intelligence-as-a-service has a ceiling. Over time, the same tensions appear: prioritization fights, loss of context, slow feedback loops. The centralized team optimizes for correctness and reuse; the domains optimize for local outcomes and timing. Both are reasonable. The interface between them becomes the problem.

What seems to work better is a shift from central intelligence to embedded capability. In these organizations: • AI capability is embedded in domains, close to the work and the decisions • Central teams focus on platforms, standards, and enablement rather than delivery • Guardrails are explicit and designed, not implicit or cultural • Ownership of outcomes remains firmly with the business, even when AI systems are involved

This shift requires building the cross-functional muscle I described in How to Build a Product Org That Can Actually Ship AI: structured rituals, clear responsibilities, and shared ownership across Product × AI Model × Design. Without this organizational discipline, teams remain trapped shipping features while competitors build compounding advantages.

This doesn’t eliminate the need for centralization — it reframes it. Platforms still matter. Shared infrastructure matters. Common approaches to risk, data, and compliance matter. But they exist to support judgment and action in the domains, not to replace them.

The result rarely looks tidy. Adoption is uneven. Practices diverge before they converge. Learning happens in public, not behind a center-of-excellence boundary. What changes is not speed alone, but accumulation.

Capability turns into habit.

What this asks of leaders

Seen this way, AI is less a technology challenge and more a leadership mirror. It reflects how decisions are made, how trust is distributed, and how much ambiguity an organization is willing to surface instead of smoothing over.

You can’t resolve that with a platform decision. You resolve it by doing the slower work: clarifying ownership, redesigning interfaces between teams, and being explicit about where judgment is expected — and where it isn’t. This starts with choosing the right problems to solve, using frameworks like the one in How to Evaluate AI Use Cases That Actually Move the Needle to ensure organizational energy goes toward initiatives that deliver measurable outcomes, not just flashy demos.

AI will continue to improve.

The harder part is deciding — deliberately — how we want our organizations to think, decide, and act with it.

That’s why AI strategy, in the end, keeps turning into an org design problem.